The Bloody Story of May Day

May Day is a May 1 celebration with a long and varied history, dating back millennia. Throughout the years, there have been many different events and festivities worldwide, most with the express purpose of welcoming in a change of season (spring in the Northern Hemisphere). In the 19th century, May Day took on a new meaning, as an International Workers’ Day grew out of the 19th-century labor movement for worker’s rights and an eight-hour workday in the United States.

Celebrations on May 1 have long had two, seemingly contradictory meanings. On one hand, May Day is known for maypoles, flowers and welcoming the spring. On the other hand, it’s a day of worker solidarity and protest; though the U.S. observes its official Labor Day in September, many countries will celebrate Labor Day on Monday.

How did that happen?

Like so many historical twists, by complete accident. To old-fashioned people, May Day means flowers, grass, picnics, children, clean frocks. To up-and-doing Socialists and Communists it means speechmaking, parading, bombs, brickbats, conscientious violence. This connotation dates back to May Day, 1886, when some 200,000 U. S. workmen engineered a nationwide strike for an eight-hour day.

A few minutes after ten o’clock on the night of May 4, 1886, a storm began to blow up in Chicago. As the first drops of rain fell, a crowd in Haymarket Square, in the packing house district, began to break up. At eight o’clock there had been 3,000 persons on hand, listening to anarchists denounce the brutality of the police and demand the eight-hour day, but by ten there were only a few hundred.

The mayor, who had waited around in expectation of trouble, went home, and went to bed. The last speaker was finishing his talk when a delegation of 180 policemen marched from the station a block away to break up what remained of the meeting. They stopped a short distance from the speaker’s wagon.

As a captain ordered the meeting to disperse, and the speaker cried out that it was a peaceable gathering, a bomb exploded in the police ranks. It wounded 67 policemen, of whom seven died. The police opened fire, killing several men and wounding 200, and the Haymarket Tragedy became a part of U. S. history.

In 1889, the International Socialist Conference declared that, in commemoration of the Haymarket affair, May 1 would be an international holiday for labor, now known in many places as International Workers’ Day.

In the U.S., that holiday came in for particular contempt during the anti-communist fervor of the early Cold War. In July of 1958, President Eisenhower signed a resolution named May 1 “Loyalty Day” in an attempt to avoid any hint of solidarity with the “workers of the world” on May Day. The resolution declared that it would be “a special day for the reaffirmation of loyalty to the United States of America and for the recognition of the heritage of American freedom.”

The connection between May Day and labor rights began in the United States. During the 19th century, at the height of the Industrial Revolution, thousands of men, women and children were dying every year from poor working conditions and long hours.

Today, May Day is an official holiday in 66 countries and unofficially celebrated in many more, but ironically it is rarely recognized in the country where it began, the United States of America.

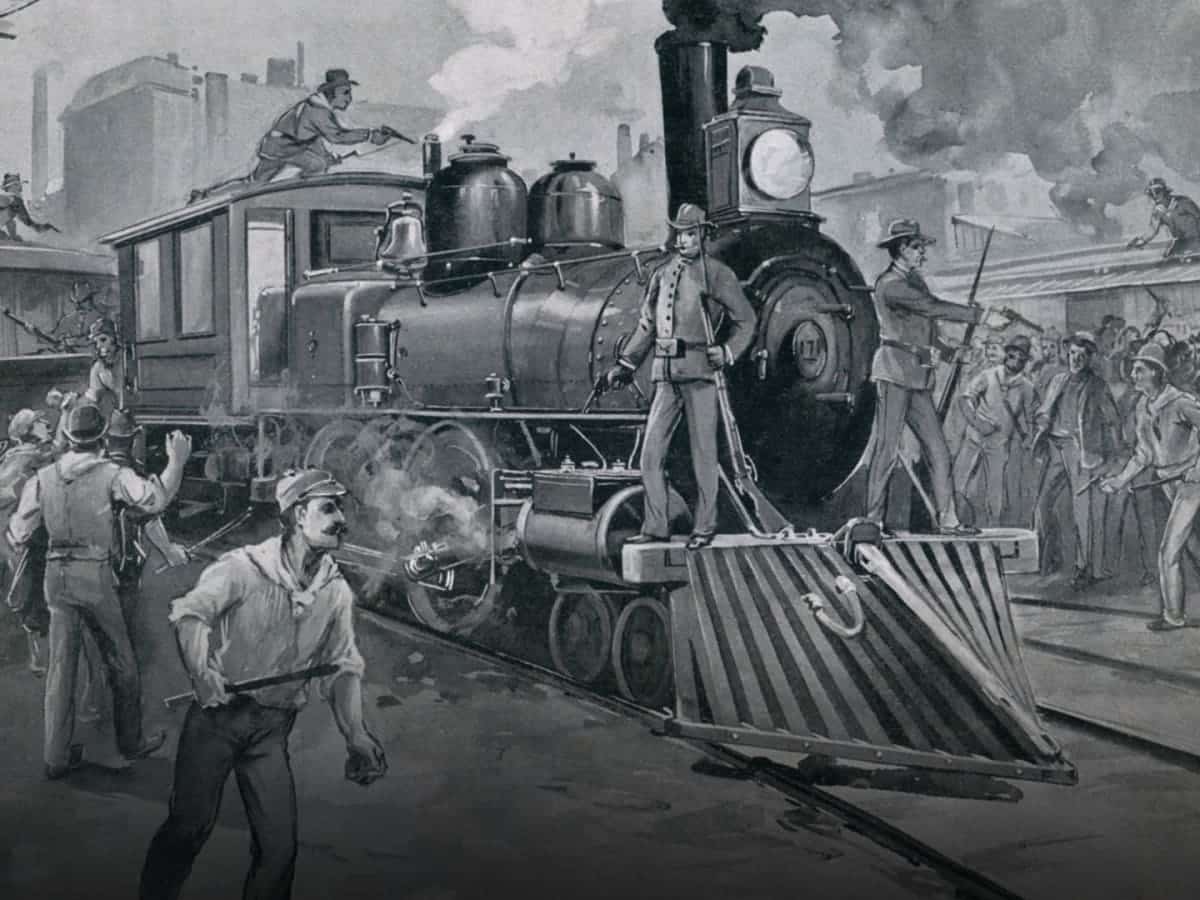

After the 1894 Pullman Strike, President Grover Cleveland officially moved the U.S. celebration of Labor Day to the first Monday in September, intentionally severing ties with the international worker’s celebration for fear that it would build support for communism and other radical causes.

Dwight D. Eisenhower tried to reinvent May Day in 1958, further distancing the memories of the Haymarket Riot, by declaring May 1 to be “Law Day,” celebrating the place of law in the creation of the United States.