Rebel poet Kaazi Nazrul Islam : A Profile Study

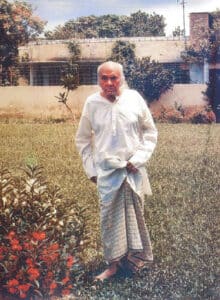

Kazi Nazrul Islam (1899 – 1976) – He is known as Bidrohi Kobi – The Rebel Poet of Bengal, The National Poet of Bangladesh, and more truly a World Poet.

Nazrul said, “Even though I was born in this country (Bengal), in this society, I don’t belong to just this country, this society. I belong to the world.” [Nazrul Rochonaboli, Bangla Academy, Vol. 4, p. 91]

He was a very versatile poet, lyricist and writer who composed many beautiful verses of poems, prose, songs and classical music.

Nazrul known as the ‘Rebel’ poet in Bengali literature and the ‘Bulbul’ or Nightingale of Bengali music, was one of the most colorful personalities of undivided Bengal. He may be considered a pioneer of post-Tagore modernity in Bengali poetry. The new kind of poetry that he wrote made possible the emergence of modernity in Bengali poetry during the 1920s and 1930s. His poems, songs, novels, short stories, plays and political activities expressed strong protest against various forms of oppression – slavery, communalism, feudalism and colonialism – and forced the British government not only to ban many of his books but also to put him in prison. While in prison, Kazi Nazrul lslam once fasted for 40 days to protest against the tyranny of the then British government.

Kazi Nazrul Islam was born on May 24, 1899 in Churulia village, Bardhawan in West Bengal, India. His mother was Zaheda Khatun and his father Kazi Fakir Ahmed was the Imaam of the local village mosque. The second of three sons and one daughter, Nazrul lost his father in 1908 when he was only 9 years old and his father died at the age of 60. Nazrul’s nickname was “Dukhu Mia” (hapless chap), a name that aptly reflects the hardships and misery of his life right from the early years. His father’s premature death forced him, at the age of 10, to become the Muazzin (a caller for prayer) of the local mosque. This early exposure to the principles and practices of Islam was to have a significant impact on his later literary endeavors.

In 1910, at the age of 11, Nazrul returned to his student life enrolling in class VI. The Headmaster of the school remembers him in the following words: “He was a small, good-looking boy, always the first to greet me. I used to smile at him and pat him on the back. He was very shy.”

Again, financial difficulties compelled him to leave school after class VI, and Dukhu Mia ended up as a cook in a bakery and tea-shop in Asansole.

In his youth, Nazrul joined a folk-opera group inspired by his uncle Bazle Karim who himself was well-known for composing songs in Arabic, Persian and Urdu. As a member of this folk-opera group, the young Nazrul was not only a performer, but began composing poems and songs himself. Nazrul’s involvement with the group was an important formative influence in his literary career.

Nazrul submitted to the hard life with characteristic courage. In 1914, Nazrul escaped from the rigors of the tea-shop to re-enter a school in Darirampur village, Trishal in Mymensingh district. Although Nazrul had to change schools two or three times, he managed to continue up to class X, and in 1917 he joined the Indian Army when boys of his age were busy preparing for the matriculation pre-test examination.

For almost three years, up to March-April 1920, Nazrul served in the army and was promoted to the rank of Battalion Quarter Master Havildar. Even as a soldier, he continued his literary and musical activities, publishing his first piece ‘The Autobiography of a Delinquent” (Saogat, May 1919) and his first poem, “Freedom” in Bangiya Musalman. Sahitya-patrika, (July 1919), during his posting at Karachi cantonment. What is remarkable is that even when he was in Karachi, he subscribed regularly to the leading contemporary literary periodicals that were published from Calcutta like, Prabasi, Bharatbarsha, Bharati, Saogat and others.

When after the 1st World War in 1920, the 49th Bengal Regiment was disbanded, Nazrul returned to Calcutta to begin his journalistic and literary life. His poems, essays and novels began to appear regularly in a number of periodicals and within a year he became well known not only to the prominent Muslim intellectuals of the time, but was also accepted by the Hindu literary establishment in Calcutta. In 1921, Nazrul went to Santiniketan to meet Rabindranath Tagore – his master-poet, the source of his inspiration…

The same year, Nazrul was engaged to be married to the love of his life – Nargis, the niece of a well-known Muslim publisher Ali Akbar Khan, in Daulatpur, Comilla, but on the day of the wedding (18th June, 1921) Nazrul suddenly backed out at the last moment, and left the place due to some serious misunderstandings and disagreements. However, many songs and poems reveal the deep wound that this experience inflicted on the young Nazrul and his lingering love for Nargis.

In 1922, Nazrul published a volume of short stories Byathar Dan (The Gift of Sorrow), an anthology of poems Agnibeena, an anthology of essays Yugabani, and a bi-weekly magazine, Dhumketu. A political poem published in Dhumketu in September 1922, led to a police raid on the magazine’s office, a ban on his anthology Yugabani, and one year’s rigorous imprisonment for the poet himself.

On April 14, 1923, when Nazrul lslam was transferred from the Alipore jail to the Hooghly jail, he began a fast to protest the mistreatment by a British jail-superintendent. Immediately, Rabindranath Tagore, who had dedicated his musical play, Basanta, to Nazrul, sent a telegram saying: “Give up hunger strike, our literature claims you”, but the telegram was sent back to the sender with the stamp “addressee not found.”

Nazrul broke his fast more than a month later and was eventually released from prison in December 1923. On 25th April 1924, Kazi Nazrul lslam married a Hindu woman Pramila Devi and set up his residence in Hooghly. An anthology of poems ‘Bisher Banshi’ and an anthology of songs ‘Bhangar Gan’ were published later this year and both volumes were seized by the government. Nazrul soon became actively involved in politics (1925), joined rallies and meetings, and became a member of the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee. He also played an active role in the formation of a workers and peasants party.

In 1926, Nazrul went and settled in Krishnanagar. His patriotic and nationalistic songs expanded in scope to articulate the aspirations of the downtrodden classes. His music became truly people-oriented in its appeal. Several songs composed in 1926 and 1927 celebrating fraternity between the Hindus and Muslims and the struggle of the masses, gave rise to what may be called “mass music”. Nazrul’s musical creativity established him not only as an egalitarian composer of “mass music”, but also as the innovator of the Bengali Ghazal.

The two forms, music for the masses and ghazal, exemplified the two aspects of the youthful poet: struggle and love. Nazrul injected a revitalizing masculinity and youthfulness into Bengali music. Despite illness, poverty and other hardships, Nazrul wrote and composed some of his best songs during his Krishnanagar stay.

From 1928 to 1932, Nazrul became directly involved with His Master’s Voice Gramophone Company as a lyricist, composer and trainer, and many records of Nazrul songs, sung by some of the most well-known singers of the time were produced. The newly established Indian Broadcasting Company also enlisted Nazrul as a lyricist and composer and he remained actively involved with several gramophone companies and the Radio till his last working days. Nazrul songs were in great demand on the stage as well. He not only wrote songs for his own plays, but generously provided lyrics and set them to tune for a number of well-known dramatists of the time.

In 1929, a colorful national reception was accorded to Nazrul in Calcutta and was attended by prominent people like the scientist Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray, Barrister S. Wajid Ali and Subashchandra Bose.

In the midst of these productive activities, tragedy struck twice in rapid succession: first, Nazrul’s mother died in 1928; a year later, his 4 year old son Bulbul died of small pox, five months after the birth of his second son Shabyashachi.

Between 1928 and 1935, Nazrul published 10 volumes of songs containing over 800 songs of which more than 600 were based on classical ragas, almost 100 were folk tunes and kirtans and some 30 were patriotic and other songs. Thus during the 1930s, Nazrul established a firm classical foundation in Bengali Music. His songs dealt with the themes of love, nature, divinity and nationalism.

In 1936, the film Vidyapati was produced based on Nazrul’s recorded play. In the same year, Rabindranath Tagore’s novel Gora was filmed with Nazrul as its music director and included one of his own songs. In June 1936, Sachin Sengupta’s important play, Siraj-ud-daulah was staged. The songs and music were written and directed by Nazrul. The play and songs met with such unprecedented success that a gramophone recording was made, and at that time was commonly heard in almost every Bengali household.

In October 1939, Nazrul’s relationship with Calcutta Radio was formalized, and numerous musical programs were directly broadcast under his supervision. Worth mentioning are the critical and research oriented programs such as “Haramoni” and “Navaraga-malika”.

During 1939, different recording companies issued a total of over 1000 records, 1648 of which were Nazrul’s songs. The total number of his unrecorded songs is perhaps twice as much. Nazrul’s songs were also broadcast from Dhaka Radio. This trend continued throughout 1941, with songs based on many different ragas and narrative ballads. Apart from these, Nazrul occasionally took part in recitation and commentary of the Holy Ouran.

In early 1941, Sher-e-Bangla Fazlul Huq commenced re-publication of the daily newspaper Nabayuga (“New Age”). Nazrul was its Chief Editor returning to the world of journalism at the final stage of his active life. On August 8th 1941, Rabindranath Tagore died. Nazrul spontaneously composed two poems in Tagore’s memory, of which one was broadcast and recorded on gramophone. Within a year, Nazrul himself fell seriously ill and gradually lost his power of speech, being stricken by cerebral palsy. Thereafter from July 1942 till his death in August 1976, the poet spent 34 years in mute silence unable to speak even a single word.

In October 1942, mental dysfunction set in and Nazrul was admitted to Lumbini Park Mental Hospital in Calcutta, but there was no improvement in his mental condition and he began losing his memory. By then, despite having earned lavish sums through his music, he had also spent recklessly and was in financial difficulties. Many of his old friends turned away in this dark hour, and he became increasingly embittered, as evidenced in this letter to a friend Zulfikar Haider on July 17, 1942 :

…I am bed-ridden due to blood pressure. I am writing with great difficulty. My home is filled with worries: illness, debt, creditors; day and night I am struggling.

…My nerves are shattered. For the last six months, I used to visit Mr. Haque (A. K. Fazlul Haque, the then Chief Minister of undivided Bengal) daily and spend 5-6 hours like a beggar…I am unable to have quality medical help…

This might be my last letter to you. With only great difficulty, I can utter a few words. I am in pain almost all over my body. I might get money like the poet Firdausi on the day of the funeral prayer (janajar namaz).

However, I have asked my relatives to refuse that money.

Yours,

Nazrul

Source: Dr. Sushilkumar Gupta, Nazrul Choritmanosh (Calcutta: De’s Publishing, 1960), p. 106]

Nazrul entered a world of increasing isolation, though still revered by Bengalis. In 1945, Calcutta University awarded him the “Jagattarini Gold medal”. In 1952, he was transferred to the Ranchi Mental Hospital from where he was sent to London for treatment at the initiative of the “Nazrul Treatment Society” formed and financed by some of his ardent admirers when they came to know of his financial hardships.

Several eminent physicians in London including Sir William Sargent, were of the opinion that his initial treatment had been inadequate and incomplete. Thereafter, Nazrul was taken to Vienna where his condition was diagnosed as incurable. He and his family returned to India in December 1953. He spent the rest of his life in utter misery.

Earlier his wife, Pramila Devi, had become ill in 1939 and though paralyzed from the waist down, she spent the next 23 years of her life, caring for her husband until her death at the age of 54 on 30th June, 1962. As per her last wish, she was buried at her husband’s birthplace, Churulia. [Nazrul’s sons, Aniruddha died in 1974 at the age of 43, and Shabyashachi in 1979 at the age of 50.]

In 1962, Nazrul was awarded the ‘Padmabhushan’ Title by the Govt. of India. In 1969, Rabindra Bharati University honored him D. Lit Degree. In Nazrul’s opinion, the highest recognition he ever cherished was when his master-poet, the inspiration of his life, Rabindranath Tagore dedicated his “Bashanto” opera to Nazrul, saying that Nazrul had ushered in Bashanto (Spring) in the life of the Nation, thus recognizing him as a wonderful poet.

When in sound health, Nazrul had earlier come to Dhaka in December 1940 to attend the 1st anniversary of the Dhaka radio station. In 1971, the Government in exile of Bangladesh continued to pay the pension due to him by the Government of East Pakistan. After the liberation of Bangladesh, at the request of the Bangladesh Government, the Government of India allowed Nazrul to be taken for residing in Bangladesh with his family.

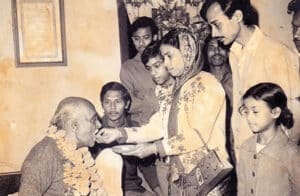

Nazrul arrived on 24 May 1972, as guest of the Government of Bangladesh and was accorded due honors. The President and Prime Minister paid their homage to him. In 1974, the Dhaka University awarded him the degree of Doctorate of Literature. In 1976, the Government awarded him the “Ekushey Padak” Gold Medal.

On 22 July 1975, Nazrul was transferred to the Post Graduate Hospital for continuous medical supervision. He spent the remaining one year, one month and eight days of his life there. Towards the end of August 1976, his condition deteriorated, his temperature shot up to over 105 degrees, and on 29 August 1976, he breathed his last at 10:10 a.m.

As soon as Nazrul’s death was broadcast over Radio and T.V. the news spread like wild fire and plunged the Bengali nation in profound gloom. Life came to a standstill in Dhaka as thousands of men and women lined up to have a last glimpse of the rebel poet’s mortal remains in the Teacher-Students’ Centre of the University of Dhaka.

At 5 p.m. on the same day, Kazi Nazrul Islam was buried with full state honor beside the Dhaka University mosque. Now almost three decades after his death, Kazi Nazrul Islam resides in the hearts of millions of Bangladeshis as their national poet.

Emerging from the overall backwardness of the Muslims of Bengal in the 1920s, Nazrul injected the community with a much-needed sense of self-confidence. Almost single handedly, Nazrul brought about a renaissance amongst Bengali Muslims, and led them into modernity. The genius of Nazrul achieved the impossible and the Bengali nation remains eternally indebted to him.

Bangladesh honored itself by honoring Kazi Nazrul Islam with the citizenship of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Now, the world over, Nazrul is known as the National Poet of Bangladesh.

By the time he passed away in Dhaka on August 29, 1976 — having spent 34 years in paralytic torment – he had become a legend, the exemplar of a religious sensibility that was not bounded by abstract definitions, but defined itself in the acts of devotion, empathy and creativity. He was the Rebel Poet. His humanistic vision, philosophy and spirit transcended many orthodox boundaries. He was also a very down-to-earth, maatir-manush, his communication so simple and straight-forward that could be understood by the masses.

In those days of India’s struggle for Independence and Undivided Bengal, Nazrul always believed in the strength of Hindu-Muslim Unity. Being a Muslim, he himself married a Hindu Woman, Pramila Devi, and also wrote devotional songs – Shyama Sangeet – dedicated to the Hindu Goddess – Ma Kali. He deserves to be known as a very versatile poet, lyricist and writer. He was a mass-oriented, revolutionary, literary figure, always protesting against bigotry, injustice, extremism, fanaticism, exploitation, oppression and inequality of all kinds. He was a bold and undaunted activist always feared by the establishment. He was a passionate advocate of religious harmony always advocating better hindu-muslim relationships. Through his songs and poetry, he propagated the universal values of love, peace, tolerance, freedom, justice, harmony and cooperation. As a persona, he had an indomitable human spirit and was full of love, valour, creativity, humanity and romanticism. He was very warm-hearted and loving and could express his feelings in the most beautiful way through his writings.

The Rejected Blood

[Excerpts of 2 letters Kazi Nazrul Islam wrote to Kazi Motihar Hussain, Nazrul Rochonaboli, Bangla Academy, Vol.4, pp. 416, 420]

Dear Motihar,

Recently, something interesting happened. Nothing big, but I thought I would mention it. There was an Ad in the Daily Bosumoti a few days ago that there is a Brahmin gentleman in his deathbed. He might live if donation of blood from a healthy, young person is given to him. He lives, right here, in Kolkata. I have agreed to donate blood. Today the doctor will examine me. He will take blood from me for transfusion. Nothing to be afraid, but I have to take rest for couple of days. I would let you know what happens. Please don’t mind if my letter-writing is delayed a few days.

As a friend, I have a request. Please don’t let anyone know about it.

Dear Motihar,

I didn’t donate blood. That doctor-fellow says: my heart is weak….I felt like giving him a punch to show how weak is the heart. The real issue is altogether different. The Brahmin gentleman did not want to accept the blood of a Muslim. Alas humanity; alas, its religion! Anyway, no Hindu youth has come forward to donate blood. The guy will die, but won’t accept the blood of a “Nere”! (muslim of low status)

Nazrul’s Flowery Tribute to Life and Beauty:

For conferring on me the honor as the chair of this Eid conference, I offer my gratitude to the Bengal Muslim Literary Society (Bongio Musalman Shahitto Shomiti). Let me first offer you my Eid greetings. Eid is the celebration of joy and sacrifice.

Today, this is a poetry conference. Poets and writers have gathered here. Poets, writers, musicians are messengers who bring to people the message from the realm of joy and beauty. That’s why they are the pride of human civilization. The human thirst for joy and beauty is eternal. Just as a person feels hunger for food, so he does feel thirst for beauty…The poets are there to quench the thirst of the non-poets. The demand for the beauty dimension of life co-exists with the ordinary needs of people’s life. One day I observed a person returning from the market, holding a hen in one hand and some Tuberose (Rajanigandha) flowers in the other. I complimented him saying, “I have never seen such a combination of Fair and Fowl (foul) together!”

The duty of delivering the cup of beauty-ambrosia is on the shoulders of poets and writers. Lot of hardship and suffering, the writers face in this path, but they must not be afraid. Through growing trees and paddy (rice), people turn acres and acres into plantations, but how many undertake cultivation of roses? It is even more unfortunate that the thirst for the beauty is so scanty among the educated ones of this land. It’s no wonder that the poet-writers of this land have to struggle so much in their life. But let’s not despair. The blows of pain must be welcomed with the visits of joy. The life and works of the poets and writers are like Lotus. Each of its petals has bloomed because of being stricken with so much pain and suffering.

I vividly remember my great feeling and realization of this one day in life. My son passed away. My heart was broken by the deep sadness at this loss. That day, I found Hasna-Hena (a flower) blooming in my house. I smelled the fragrance of that Hasna-Hena to my heart’s delight. That’s the way to enjoy life – that’s living a full life. I have cherished the experience of this very kind of life. My poetry and music have emanated from my life’s experiences. I sang with the rhythm of life – these are the expressions of that rhythm. Whether my poetry and music are great or mediocre, I don’t know. But I want to state emphatically – I have lived my life fully. I have never dreaded pain or suffering. I have dived into the ocean waves of life.

I was the first in my class. The headmaster had great hope that I would bring more honor to the school, but the world war of Europe came along. One day I saw people going to war. I also joined a platoon. I went to Chattogram, saw the sea, and I thoroughly enjoyed my life by diving into it. One day a policeman aimed his pistol at my forehead, while standing right in front of me, and said, “I can kill you.” I exclaimed: “Friend! Indeed, I have been searching for death all along…”

[Excerpts from an address “Shwadhin-Chittotar Jagoron”, given in 1940 in Calcutta Eid gathering of Bongio Musalman Shahitto Shomiti. Nazrul Rochonaboli, Vol. 4, 1996, p. 115.]

(compiled from various sources)