October 9, 1967 : Che Guevara is executed

Guevara, the beret-wearing guerrilla leader who had led firing squads after the Communist victory in Cuba, had abruptly resigned from his government posts and left Cuba to spread the revolution in Africa and South America. But the missions, including the one to arouse an uprising in Bolivia, were all but doomed. On that afternoon of Oct. 8, 1967, Guevara was taken prisoner and carried by soldiers to a one-room schoolhouse in the town of La Higuera in Bolivia, about four miles away from where he was captured, according to Richard Harris’s biography, “Death of a Revolutionary: Che Guevara’s Last Mission.”

Félix Rodríguez, a Cuban American CIA operative posing as a Bolivian military officer, would find him covered in dirt inside that schoolhouse the next day. His hair was matted, his clothes were torn and filthy, and his arms and feet were bound. The U.S. government wanted him alive to be interrogated, but Bolivian leaders decided that Guevara must be executed, fearing a public trial would only garner him sympathy. The official story would be that he was killed in battle.

Rodríguez, who was instrumental in Guevara’s capture, had mixed emotions at that time, as he acknowledged later in an interview. Here was a man who had assassinated many of his countrymen, Rodríguez said, and yet he felt “sorry for him.”

Then, he told the guerrilla leader that he was about to die.

“I looked at him straight in the face, and I just told him. . . . He looked straight to me and said: ‘It’s better this way. I should have never been captured alive,’ ” Rodríguez recalled during a “60 Minutes” interview years later.

Then Rodríguez left, ordering a soldier to shoot below the neck because that would fit the official story that Guevara had died in combat.

Guevara’s last words were to Sgt. Jaime Terán, the soldier ordered to shoot him, according to journalist Jon Lee Anderson’s biography, “Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life.”

“I know you’ve come to kill me,” he said. “Shoot, you are only going to kill a man.”

Terán fired, striking Guevara in the arms, legs and thorax.

The guerrilla leader, loved and idolized by many but hated by others, died 50 years ago Monday, at age 39.

Before Guevara was secretly buried in a mass grave, Bolivian soldiers laid out his scrawny body and put it on display for the media in the Bolivian village of Vallegrande. His corpse was placed on a hospital laundry sink as photographers took pictures that were later published internationally. The Bolivian commander also ordered both of Guevara’s hands cut off so authorities could run his fingerprints and give Castro undeniable proof that his ally was dead.

Certainty of Guevara’s death did not reach the United States until a few days later. A short memorandum written by adviser Walt Rostow to President Lyndon B. Johnson on Oct. 13, 1967, said: “This removes any doubt that ‘Che’ Guevara is dead.”

An Oct. 12, 1967, State Department report, titled “Guevara’s Death — The Meaning for Latin America,” described Guevara as “the foremost tactician of the Cuban revolutionary strategy” who “will be eulogized as the model revolutionary who met a heroic death.” That prediction materialized a week later, when Castro delivered a eulogy to a massive crowd at Havana’s Plaza de la Revolución.

“They are mistaken who believe that his death is the defeat of his ideas, the defeat of his tactics, the defeat of his guerrilla concepts,” Castro said, referring to the United States.

Ernesto Rafael Guevara de la Serna was born to a well-off family in Argentina in 1928. While studying medicine at the University of Buenos Aires, he took time off to travel around South America on a motorcycle; during this time, he witnessed the poverty and oppression of the lower classes. He received a medical degree in 1953 and continued his travels around Latin America, becoming involved with left-wing organizations. In the mid 1950s, Guevara met up with Fidel Castro and his group of exiled revolutionaries in Mexico. Guevara played a key role in Castro’s seizure of power from Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959 and later served as Castro’s right-hand man and minister of industry. Guevara strongly opposed U.S. domination in Latin America and advocated peasant-based revolutions to combat social injustice in Third World countries.

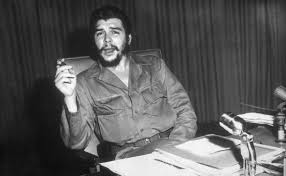

Guevara’s face, with his thick black hair, scruffy beard and familiar beret, has been printed on T-shirts, walls and banners.

Anderson, the New Yorker staff writer and Guevara biographer, described Guevara as someone who was charismatic, but also arrogant, cold and moody. He was a fearless leader, but he was also a reckless man who, in his late 30s, decided to leave his family without a guarantee that he would return.